Blydyn Square Review

Winter 2022 – Kenilworth, New Jersey

Winter 2022 – Kenilworth, New Jersey

I know a lot of people hate this time of year. Some even get full-on depressed with seasonal affective disorder when they don’t get enough light during the winter months. Not me. To say I prefer the colder months—fall and winter—to the warm ones would be an understatement.

The cool, crisp air makes my brain feel speedier than a racehorse and makes everything seem clean and fresh and full of possibility. The heat (and humidity), on the other hand, make me feel stupid and slow and sluggish.

But that’s not the point.

The point, for all your writers out there, is that, right now, we’re in a time of change (at least, those of us who live in geographical locations with actual seasons are). And there’s nothing better than change to get the writing juices flowing.

It’s all too easy when we’re working on a piece of writing to get mired down in the slow-moving slog, to lose sight of how much we love the process and simply go through the motions.

I know from experience that sometimes you get so sick of the project, so sick of waiting for inspiration, so sick of being alone with your thoughts, that you need a blast of fresh air to wake you up from your self-induced writing coma.

And that’s what the change of seasons can do—literally, yes, if you get out there in the cold winter air, but figuratively, too.

So, use it. Use the changing seasons to help yourself fall back in love with writing.

Go for a walk. Look around. Record it all and write about it:

The mounds of snow that used to be white but have turned into a sludgy black mess thanks to exhaust from the traffic. The sad-looking Christmas decorations that are STILL hanging out on your neighbor’s lawn. The bright red cardinal searching for seeds under a patch of snow beside an evergreen.

Whatever you find out there, embrace the season, use the images and the scents and the sounds you encounter, and then get back to the writing, this time with a whole new attitude.

And when you’re done, read the winter issue of Blydyn Square Review for a little more inspiration!

Use the links below to jump to the different articles

Jeffrey Hantover is a writer living in New York.

Quiscalus quiscula. The syllables dripped from my tongue like hot fudge. My five-year-old granddaughter thinks they are the funniest words she has ever heard. She giggles trying to get her mouth around the grown-up word ornithologist. She wants to know again how grandpa became a bird scientist.

I was thirteen. One October Saturday, I was raking the leaves by the glassed-in porch that ran along the south side of our house. I saw a dark-colored bird cradled in the dense branches of the shrubs bordering the porch. The bird, nameless to me, must have smashed into the glass. I was sure it was dead. I mimed for my granddaughter my trembling, tentative fingers as I lightly touched it. I was surprised to feel its iridescent chest rising and falling. I picked it up and laid it gently on the ground as if it were a ticking bomb. I sat cross-legged on a pile of leaves and waited, not sure what to expect. I ran a finger lightly down the edge of one of its wings. “Don’t die,” I whispered; “you can make it.” Like a Looney Tunes character, it shook dancing stars from its purplish-black head before crooking its head, gave me a thank-you nod, and took flight. I was sure my words had given the bird life. I finished my raking quickly, got my bike from the garage, and pedaled to the library eight blocks away. How fast did you pedal? My granddaughter wanted to know. Very, very fast, I said. Among the Icterids of the Nearctic region (the name like those of aliens from a distant galaxy), I found drawn with a fine line and color my resurrected grackle, Quiscalus quiscula. I checked out an armful of books and put them in my bike basket. And that was how grandpa became a bird scientist.

A good story. My granddaughter loved it. It was all a lie.

***

Thirteen in 1958 wasn’t your thirteen today. Lincoln Logs, Archie and Jughead, sock hops, romantic songs by Johnny Mathis, the coolness of Kookie on 77 Sunset Strip. No zombies, no Terminators and Predators, no language on TV that would have kept your mouth tasting soap for a week. We were just normal Midwestern boys growing up in Kansas City, going through phases: crashing basement parties, soaping a few car windows on Halloween, and the more adventurous sneaking off to the burlesque house downtown when your parents thought you were at the Brookside theatre watching a Randolph Scott movie. Good kids, some louder than others, some with short fuses and swelled heads, a few quick to dare you to do something stupid, that when push came to shove, they weaseled out of. We turned out okay—a fair share of lawyers, doctors, businessmen. Everyone but Billy Lanier. He never gave himself a chance.

My father’s parents lived two blocks from the old Armour Hills Golf Club, fated for ranch houses and spindly wind-whipped cul-de-sacs when I was fifteen. At seven, I walked along the sidewalk that bordered the third fairway with my cousin Mitch, a skinny, gangly nine-year-old. We were looking for stray balls that bounced through the link fence into the thick shrubs running the length of the block. All we ever found were practice balls, daubed with red paint, slashed and puckered. Mitch spied through the shrubs a hole beneath the fence that a dog must have dug. He convinced me without much effort that with a bit of scooping, we could sneak onto the course and find ourselves some unscuffed, first-class balls. We dug with sticks and rocks to make the hole bigger and crawled between the bushes. We tugged the fence up for each other and squirmed our way onto the fairway.

Under a gray, overcast sky, the fairway was a rich, emerald-green carpet that seemed to stretch forever. I saw a shining white ball a short sprint away. There were no golfers in sight. I had the ball in my hand and was turning back toward the fence when I heard someone yelling. After all these years I don’t remember the words. What I remember is my fear seeing that bobbing white cap and the screaming, beet-red face coming toward me. I dropped the ball and didn’t look back until I shimmied under the fence and was safe, far down the sidewalk.

Six years later, I crouched next to Billy Lanier behind thick bushes in the out-of-bounds off the fifth fairway. We cradled our fathers’ BB guns, snuck from hall closet and attic, waiting to shoot the tires of a passing golf cart or maybe ping metal and give the driver a hell of a scare. It was Billy’s idea of something fun to do on a lazy Saturday in late April. I went along without much coaxing, thinking it fair payback for being scared silly half a dozen years before.

Billy Lanier lived three houses down from my grandparents. We went to Thomas Nagel Elementary School together and were eighth-graders at Southwest High. Billy lived smack in the middle of the bell curve of adolescence: not first but second or third when choosing up sides for touch football or sandlot baseball, smart enough to be liked but not so brainy to be banished to the cafeteria table with the high-pocket kids with thick glasses and acne who thought the science fair was cool. At the Y dance classes, girls didn’t mince steps or take long strides hoping when the teacher called stop, they would be standing opposite Billy, but they weren’t upset when he ended up as their partner for a three-minute foxtrot.

Billy was your normal thirteen-year-old who, one Saturday afternoon when he didn’t have anything better to do or a friend smart enough to tell him “no,” blinded fifty-seven-year-old William Oester in the left eye as he reached into his bag for a five-iron.

I don’t believe in fate. But if Billy had been a better shot, he’d have hit the side of the cart he was aiming at. If Oester hadn’t hooked his drive, he never would have been near enough to get shot and none of this would have happened. Billy Lanier might have joined Lanier Buick and been president of the Rotary Club just like his dad. Three weeks after he lost his eye, Oester had a stroke and lingered for three years in mute, immobile solitude.

My father said Billy’s father called in some favors from his Rotary Club pals to keep the shooting out of the papers and Billy out of court or reform school or wherever they sent juvenile delinquents in those days. But everyone at school knew. You would have thought Billy was brother to Charlie Starkweather the way everyone that spring gave him the cold shoulder. Eighth-graders didn’t talk to him. Even juniors and seniors gave him wide berth when he walked down the halls those last weeks of school. We would pass in the halls, but Billy said little and always seemed in a hurry to get where he was going. He spoke in class only when called on. He took all his homework to his last class so he didn’t have to go to his locker and could disappear down the stairs while the final bell echoed through the corridor.

The women teachers treated him no different, but the gym teacher and shop teacher believed Billy had shown his true colors and had their eyes on him, waiting for him to screw up again and prove them right. For Craig Greenhaven, the gym teacher with a square jaw and a flattop who had blown out his arm in double-A ball, it was one strike and you were out. The world was divided into screw-ups and good kids. That Saturday afternoon, Billy crossed that line and could never get back. The shop teacher, a white-haired fellow whose name I have long forgotten, had seen enough boys to know better but thought Billy’s character a dark whorl so deep, no planing could remove it.

My uncle said it was an accident. “The boy wasn’t trying to hit him. He couldn’t hit him again in the eye with all the BBs in China if he tried.” My father was less forgiving. Billy was a bad influence and my father forbade me to invite him to the sleep-over poker games popular among us eighth-grade boys.

One Sunday while I was mowing my grandparents’ front lawn, Billy came by on his bike. Heading down the slope toward the sidewalk, I yelled at him without thinking I shouldn’t.

“You okay?” He stopped and nodded. “Once school’s out, things will be better,” I said.

He gave me a half-smile like he knew that I knew they wouldn’t. He started to pedal back home, then stopped and half-turned toward me. “I see Oester every night. Just sitting there, slobber trickling down his chin. One hand curled up like a claw in his lap. The other pointing at me like Uncle Sam . . . every night.”

I went to camp that summer in Minnesota. I heard Billy spent the summer on his uncle’s farm outside Salina, sent there to work hard, stay clear of trouble, and straighten himself out. A week before school started, Billy Lanier hanged himself with his sister’s jump rope from a pipe in his basement. I guess the thought of another year like the spring was too much for him.

***

Billy didn’t fire first. I did. The cart was on a slight rise. I was aiming for the left rear tire. I was an unpracticed shot. It could have been me who blinded William Oester, but as I pulled the trigger, a bird took flight about fifteen yards from our hiding place. The bird froze in mid-air and dropped like a plumb line in the tall grass behind a narrow sand trap. Oester was standing over his ball, gauging his shot. Billy fired. Oester howled and stumbled against the cart. His yellow gloved hand went to his eye and came back purple. His playing partner jumped out of the cart, looked at Oester, and then in our direction. He couldn’t have seen us hidden behind the bushes. Billy panicked and set off across the fairway, gun in hand. I didn’t know what to do. Things happened so fast, I didn’t have a chance to make a choice. I stayed put. Oester’s partner had the angle on Billy and tackled him before he made it across the fairway. They both lay stunned for a moment. The foursome on the fifth tee, seeing all the commotion, jumped into their carts and sped down to find out what the trouble was. They hustled Billy into a cart and headed toward the clubhouse. I hunkered down among damp leaves and branches for a good two hours. I left the gun behind and ran across the fairway back home.

The policemen I was afraid would be parked outside my house weren’t there. All I got was a warning not to be late for dinner again. After dinner, while it was still light, I biked to the course, camp duffel bag scrunched into the wire basket in front of the handlebars. I clambered over the same low fence Billy and I climbed that afternoon, retrieved the BB gun, and stuffed it in the bag.

I walked behind the sand trap. The bird was still there— a nameless, tiny, delicate creature, no bigger than my hand, with black and white striped feathers. I nudged it with the toe of my sneaker. I can’t tell you why that boy, the one I barely remember being, picked up the bird. In some way that I couldn’t have explained back then, I felt called to do it. I hadn’t paid any attention to birds until then. They were something taken for granted in a boy’s world: targets for small rocks that never seemed to hit home, things that dogs chased. They sat on telephone wires, hopped across lawns, and turned trees into song at summer twilight. They weren’t animals with lives complex and patterned. Birds were just decoration for human pleasure.

I biked back home in the fading twilight along the quiet sidewalks, the bird nestled in the duffle bag. I wrapped it in old newspapers and hid it in a cardboard box under a pile of oily rags beneath the tool board in the garage. Monday after school, I went to the library to find out its name. A black-and-white warbler, Mniotilta varia. Before I buried it in a corner of my mother’s tiny garden in the backyard, I plucked two primaries: one black feather, one white. They lay brittle and dry in a plastic bag in the middle drawer of my desk. A memento mori—a reminder of how few things in life are black and white.

For sixty years I’ve studied birds. Birds are a lot easier to understand than humans. We are quick to think someone is the worst thing they’ve ever done in their life. Intention gets lost in the rush to morally judge someone. Imagine if Lee Harvey Oswald had a cold that November morning in Dallas. He begins to cough, and the motorcade—and history—passes him by. Would he have been any less guilty for not taking the shot? He intended to kill the president. If he had taken the cough drops Marina offered that morning, he would have. Billy didn’t intend to blind William Oester. He was just guilty of being a kid and a bad shot.

Mniotilta varia changed my life. So did Billy Lanier. He told the police he was alone. Like I said, Billy was a good kid.

A. V. Griffin is a professional writer, entrepreneur, and artist who resides in Upstate New York. She is the author of two books: a sci-fi novella called The Demon Rolmar and a collection of poems called Ephemeral Thoughts. Griffin holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology and a master’s degree in library and information science. Contact her at averygriffin111@gmail.com, or buy her books online: The Demon Rolmar and Ephemeral Thoughts.

Old Man Winter stalks through the barren trees

Bringing with him Death, who sits upon a frigid breeze

Winter shows no clemency to the forest life

And only offers them a gift of strife

And when the snow begins to fall

It brings a deadly, pristine beauty for them all

And Death, now pleased with the realization of his only dream

Brings forth a horrific scene

Of frost and fallen beings

Bodies strewn everywhere, with eyes unseeing

Dead and finally gone

Their souls have now withdrawn

Death is dressed in his finest

His face beams at its brightest

And Winter, grim and gaunt

Feels mirth for what the two have brought

Time passes by painfully

Spring waiting patiently

For her chance to proceed

And undo their wicked deeds

Their reign can only last for so long

They will be undone by Spring’s gentle song

That brings life within a melody

And restores all of nature’s serenity

D.C. Briley is an author living with his family in Ridgefield, Connecticut. He can be contacted via his website at www.dcbriley.com.

It was said that Father O’Malley possessed a divine gift unlike that of other priests. If you ask any clergyman, he will tell you that at some point in his life, he heard the calling to join the priesthood. A calling that, without experiencing it firsthand, could never be understood or rationalized. Father

O’Malley’s call was especially unique: He had already received it before he was even born.

Whether by accident or by celestial intervention, Father O’Malley was destined to become one of the most famous of all of God’s messengers on Earth. There were rumors that at a very young age he was being groomed for the papacy, perhaps to become the first Pope from the United States. Despite his tiny frame, he had a gift for converting even the firmest atheist into a God-fearing person.

Whether those rumors were just that, rumors, or whether he was, in fact, chosen by God to take up the mantle, there was no denying that Father O’Malley was special.

And while you could call Father O’Malley many things, a hypocrite was not one of them. Unlike other men in positions of power, who could be tempted by all sorts of misgivings, Father O’Malley was never one to shy away from the duty of his profession. From a young age, Father O’Malley—“Pops” to his school friends—walked as virtuous a line as could be walked in this day and age. No matter the time of day, or day of the week, Pops was always helping someone.

You could count on Pops to be out there doing something, whether he was shoveling his parents’ elderly neighbors’ driveway after a bad snowstorm, assisting a struggling classmate with their algebra homework, or even helping others free themselves from the torture of their sins and walk out of the shadows and into the light. While never actually pushing Catholicism on any of his friends, until, of course he had received the Rite of Ordination, it was said that once Pops came into your life, within a week you would feel the sunshine on your face, and know that God had welcomed you into His Kingdom.

The sky was the limit for Pops (no pun intended).

That is why all who knew him found it strange that Father O’Malley, of all people, chose to work in such a menial position as prison minister at Browngate Prison, the only prison on Earth with a population consisting of only death-row inmates: 105 inmates; all ready for execution within the coming days, months, and years; all united by their abandonment of God’s love; and all unknowingly about to receive their last chance for that gift.

“I am merely a tool. Only God can judge these men—and all children of God deserve the final chance to repent their sins and beg for forgiveness so that they may spend the afterlife in the arms of the Almighty.”

That was the only answer Father O’Malley ever gave to those who asked why he chose to serve in this setting.

And so, with one week left before their executions, the inmates would have the chance to receive their Last Rites from Father O’Malley (now only known as Pops to a select few). Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu—the inmate’s faith did not matter; everyone had the opportunity to be saved.

Father O’Malley’s process was always the same: Two days before the execution, he would meet with the prisoner alone. What they discussed was never known, as this meeting was not part of the official Last Rite.

However, no matter how stubborn they were in their beliefs, one by one all of the inmates returned to Father O’Malley’s office the next day.

On the eve of their executions, Father O’Malley would have a second conversation with the prisoners and would administer Last Rites to those who asked for it, which was usually only a select few.

The prison guards had come to respect Father O’Malley, and carefully listened to any suggestions that he may have. Though it was rare, Father O’Malley was thrice able to convince the guards that a prisoner was mentally ill and ought to have been committed instead of sent to death row.

Saving a soul doesn’t always have to be in the eyes of the Lord.

It went like that, day by day, year by year, without much fanfare.

This week, however, a clerical error resulted in three executions being scheduled for the same day. There was no doubt about it: May 25 was going to be a busy day. Three inmates, all guilty beyond a shadow of a doubt, were going to be executed.

And so, as was his custom, Father O’Malley met with all three inmates on May 23.

The first prisoner was Jason Rigsby. A particularly brutal bastard, Rigsby had shamelessly gutted his brother’s three children with an old fishing knife as revenge for his brother accidentally taping over a football game from twenty-eight years ago.

Despite not believing in this God thing, Rigsby had heard the stories about Father O’Malley and decided that he would not be the first prisoner since his arrival to skip a meeting with the old priest.

As he was the first in line to be executed, an event scheduled for precisely 8:15 a.m. on May 25, Rigsby walked into Father O’Malley’s room.

Though it was a small room (it couldn’t have been any larger than a prison cell), Father O’Malley had made it seem like home. A window, situated a bit too high on the wall for much of anything useful, allowed the sun to brighten the space, and the sun’s beams directly shone onto the small coffee table located in the middle of the room and illuminated Father O’Malley’s diminutive figure as he sat waiting for his sheep.

No cameras. No guards. No candles. No crosses. Just a small man sitting in a small leather chair, looking as if he were waiting for a long-lost friend to join him for afternoon tea.

“Good morning, Mr. Rigsby,” Father O’Malley said calmly, gesturing to the empty chair across from him, his warm demeanor quelling any doubts Rigsby had had about the process.

“Forgive me, Father, for I have skinned,” Rigsby responded, simultaneously lowering himself into the comfortable chair, awkwardly trying to regurgitate a saying he had once heard in an old television show.

Father O’Malley couldn’t help but smile at Rigsby’s attempt.

“My son, this is not a confession, but thank you for being such an open-minded individual and speaking with me here today. You’ve probably heard the stories about me, but all I have to say to you this morning is that there is nothing for you to worry about. I have only one question for you: ‘If there was one thing that you could change about your life, what would it be?’”

Rigsby, somewhat taken aback by the casualness of the conversation, began to answer. But before he had a chance, Father O’Malley stopped him.

“No. Just think about it. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Before he had time to process Father O’Malley’s request, Rigsby was already back in his cell, contemplating the strange little priest’s message.

By 12:15 p.m., the second prisoner was ready to meet with Father O’Malley. John Burle, a man who was just as short as Father O’Malley but double in weight, had the exact same conversation with Father O’Malley. And then, at 2:30 p.m., Brian Dorman, the final prisoner to be executed on Wednesday, had his time with Father O’Malley, again, almost word for word (though neither Burle nor Dorman attempted Rigsby’s awkward confession).

The next day, the eve of the executions, all three prisoners were ready to meet with Father O’Malley for the second time, eager to tell him what their evening in thought had brought about.

In keeping with the order of the executions, Rigsby went first.

He walked into the same room as before, only this time, things were different.

There was no window, coffee table, or leather chairs. This time, when Rigsby entered, all he saw was a large crucifix, and one of God’s most loyal defenders praying to the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

“Father, I . . .” Rigsby began to say, as excited to share his thoughts as he was perplexed by the sudden reorientation of the room.

Father O’Malley raised a hand to stop Rigsby, and silently directed the prisoner to kneel down next to him before the cross.

“My son, what happened after we spoke yesterday?”

Rigsby knelt down.

“I went back to my cell and thought about what we discussed. I decided that if I could change one thing in my life, it would have been to run away from home when I was fourteen, so that I would never have known my brother’s children, and that they could have lived a long life. When I woke up this morning, I felt at peace. In my dreams, I saw my brother’s children playing in a field.”

Father O’Malley smiled at this answer.

“My son, this was your last test. God loves and cares for you, and has never left your side. He wants all his children to join him in the Kingdom of Heaven, but only those who truly repent and seek His forgiveness will ever be allowed to join Him. That is why He has asked me to test you, by making you think about the one thing that you would change. If your heart is pure, your desire to change is unselfish, and you repent your sins, then He will welcome you into His fold. Your dream was proof that your heart is pure, and that tomorrow, you will see Him. Your brother’s children are alive and well, and will live a long and healthy life without ever having known you. That was no dream.”

Rigsby broke down and began to weep. Father O’Malley comforted him and performed the Last Rites. With his eternal soul at peace, Rigsby left the room, comforted in knowing that he was forgiven, and that he would be in the arms of the Almighty within a short period of time.

While Burle was scheduled second for the day of the executions, there was an issue with his meeting with the warden, so instead Dorman was up next.

At six feet, five inches, Dorman towered over anyone who had the misfortune of knowing him. When he entered the room, he did not see any of the same things that Rigsby had seen. Instead, he just saw a tiny man, sitting on a chair in a dark room.

“That was a waste of time, Father. I did what you said, and thought long and hard about what I wanted to change. And I came up with the only thing that made sense: not getting caught! Which was cool, because I had a dream that I escaped that police chase that done killed those kids, but then spun out of control and those kids ended up dead anyhow.”

“My son,” Father O’Malley said. “I will pray for you. God loves you, and wants you to repent your sins for the sake of your eternal soul. But He will only allow you to enter His Kingdom if you truly seek forgiveness. I was asked by Him to test your soul, to give you a chance to see what would have happened if you could change one thing, and yet the end result was never in doubt. I beg of you, please allow me to take your confession so that your immortal soul may enter the Kingdom of Heaven tomorrow.”

“Yeah, whatever,” Dorman responded, and walked away, his soul forever lost.

Father O’Malley could only sit and pray, and he hoped that, before Dorman met with St. Peter tomorrow, he would see the error of his ways, and seek God’s forgiveness. Father O’Malley then sat back down and waited for his final appointment of the day.

Time moves slowly in a prison, but it’s even slower when you’re waiting for someone.

By midnight, Father O’Malley was forced to concede that for whatever reason, Burle was not going to show up.

Ordinarily, Father O’Malley would just return to his cottage on the other side of the grounds, put on a cup of tea, and call it a night. Tonight, though, he felt uneasy knowing that one of his flock had not yet had the opportunity to repent, and more importantly, to take his last test in the eyes of the Lord. Still wounded by Dorman’s refusal, Father O’Malley, with determination in his eyes, adjusted himself in his chair, preparing to wait for as long was necessary.

And so he waited. The silence was deafening, but Father O’Malley kept at it until, finally, at 3:00 a.m., salvation, or what looked like it, approached.

In the distance, Father O’Malley saw a smallish figure approaching, wearing clothes so large that the man looked like a toddler wearing one of his father’s suits. Beside him were two guards.

“Hiya, Pops,” said the figure, in a hauntingly calm voice.

“My son, I . . .” Father O’Malley was stunned. Although the man in front of him as undoubtedly Burle, he looked as though he had lost a hundred pounds overnight.

“Sorry for the delay, Father,” said one of the guards. “It appears that the prisoner experienced some sort of medical miracle and lost half his body weight in a matter of twenty-four hours. We needed to get him checked out before we let him see you.”

“It’s quite all right, Steven.”

The guards pushed Burle into Father O’Malley’s room, and, at Father O’Malley’s request, shut the door behind him.

“My son, what has happened to you?” Father O’Malley asked Burle, more concerned at the moment about the prisoner’s physical body than his eternal soul.

“You already know, Pops, don’t you? Your little test. Well, at first I thought about all those lives I took, and how much I missed the chase. You remember my story, right? How I would find my prey, stalk them, copy their mannerisms, steal their identities? Only after I would drown them, of course. Well, that was too much fun, so why would I want to change that?

“So, I started thinking, and I decided that the one thing I would change would be to start exercising with you once I got here so that I can live a long and healthy life. I wasn’t always fat. That only happened once I got here, so I figured I wanted to change that. Then I had a dream that I started working out with you, and you told me the story about how everyone used to call you ‘Pops,’ and I woke up like this.” Burle opened his arms wide, gazing down at his own slim figure.

Father O’Malley smiled. “I am happy to hear that, my son. This change in appearance is commendable, and I dare say that we almost look alike now. Tomorrow, as your eternal soul leaves your body, you will be—” Father O’Malley stopped short. “What do you mean by a long and healthy life?”

“Well, I didn’t say that I wanted to live a long healthy life as me.”

In one quick motion, Burle grabbed Father O’Malley and strangled him until he was no longer conscious. Carefully placing the body down, Burle stripped Father O’Malley of his robes, and executed a swift change of clothes. Burle, dressed as a pious man of God, left the room to track down the guards.

“Steven, my son, it appears that Burle is unwell. I think this medical phenomenon has sickened his mind,” Burle said, pointing through the open doorway, to the unconscious body of Father O’Malley on the floor.

“My God! Are you all right, Father?” Steven asked, as he and his partner rushed to the lifeless body to check for vital signs. The priest was alive, but unconscious.

“Quite all right, son. We were in the middle of a silent prayer, when out of nowhere, Burle, convinced that he was the real Father O’Malley, started screaming and then suddenly passed out. Please, protect him, take care of him, and make sure he is not executed tomorrow. I recommend isolation in a medical facility right away. Bless you, my son.”

“I will take care of it, Father. Will you be okay?”

“Oh, yes.” Burle smiled as he headed toward the door. “Though I may be a bit late tomorrow.”

To the outside world, John Burle spent the rest of his life confined to his cell, screaming to whoever would listen to him that he was Father O’Malley. Father O’Malley, the man who would be king, was never heard from again.

Sarah Butkovic is a recent graduate of Dominican University who is currently pursuing her master’s in English at Loyola University in Chicago. As a longtime lover of thrillers and an avid reader of Nancy Drew novels and Stephen King growing up, Sarah intended for this story to be a conglomeration of her two childhood loves. This is her fourth creative publication, and she is looking forward to many more!

Mrs. O’Meara had been ramblin’ on about the same story for the past ten minutes. I listened to her intently the first time, watchin’ her lips flail around like two pink worms shoutin’ the same phrase: My son’s gone missing, my son is gone! I just sat there sippin’ a cup of joe hot enough to take a layer off my tongue and noddin’ my head as the ferocious black liquid eroded my taste buds. Every now and then I slipped in a few words like “Uh-huh” and “Yes, ma’am,” just to make sure Mrs. O’Meara knew I was payin’ attention. The damn woman kept goin’ ’til her lungs deflated.

From what I gathered, her precious little Rodney never came home Friday night after work. He’d been burnin’ the midnight oil every day of the week that ended with a Y (except for the occasional Sunday that was reserved for the Big Man upstairs) but was stayin’ with his momma until he had enough dough to move out.

Understandably, Mrs. O’Meara had a panic attack on Saturday when she woke up to an empty house. She called all Rodney’s friends and coworkers to ascertain his whereabouts and then had an even bigger panic attack when she realized her son hadn’t reached out to anybody durin’ the night. The paranoia only escalated when Monday reared its ugly head and he still hadn’t come home.

She described her son as lanky with a lopsided gait. Pale as prepackaged cookie dough with eyes bluer than the Democratic donkey, always carryin’ an expression shrewd enough to turn even the most innocent onlooker to stone. From that description alone he sounded like a druggie to me, but I bit my coffee-singed tongue. It ain’t my place to make insolent remarks like that to a frantic momma.

“You promise you’ll look for him?” Mrs. O’Meara shifted uncomfortably in her seat.

“Of course.”

“Really? ’Cause I know what you must think. I can tell by that glazed-over look ya got on ya. You’re probably thinkin’, get a load of this one. This nutty woman, whinin’ and cryin’ over her twenty-four-year-old son like he’s a little schoolboy. But I promise that somethin’ here ain’t right. It ain’t like Rodney to go AWOL. His phone was goin’ straight to voicemail and now it don’t even ring. Just promise me you’ll do somethin’.”

I tapped the chintzy metal of my sheriff badge. “With all due respect, I don’t wear this thing for nothin’, ma’am. I’ll sniff around as soon as I get the chance. Scout’s honor.”

“All right,” she said hesitantly. “Ya got all my notes?”

“I got all your notes.”

Mrs. O’Meara seemed content with my flimsy promise and stood up swiftly to leave, the cadence of her movements makin’ her blubber jiggle like water in a plastic bag. I watched her hobble away into the unforgivin’ Nebraskan sun before turnin’ to the jumble of chicken-scratch I scribbled on my notepad.

As much as I didn’t want to admit it, I wasn’t used to actual detective work. In a small town like Norfolk, the biggest blunder of the year was some poor slob gettin’ their windshield shishkabobbed by an elk or an evangelical cult preachin’ nonsense on a soapbox. Solvin’ crimes may have been part of the job description, but at this point it was out of my wheelhouse.

A weighted sigh escaped me then, my hot breath tricklin’ down the front of my shirt collar.

I sure had a lot of work to do.

***

First order of business was scopin’ out Rodney’s place of employment. The cops on TV shows always went to the last place their victims were seen alive, so I figured it’d be best to do the same.

Turns out, Mr. O’Meara spent his nine-to-five cooped up in a miserable Wonderbread cubicle workin’ for some hoity-toity lawyer named Wayne Wallburg. Rodney and a bunch of other law-school dropouts were slaves to the company mailroom, constantly typin’ up a bunch of legal gobbledygook and deliverin’ letters to employees higher up on the corporate ladder. If this job was the reason he ran away, I sure as hell couldn’t blame him.

His coworkers—all whiter than a pack of Saltine crackers and dumber than door knobs—were completely useless to the investigation. They either didn’t care enough to remember what Rodney was up to or were too braindead to recall even the slightest detail from Friday afternoon. The biggest break I got was from his desk partner, Corey, who mentioned that Rodney joined a new church last month. Some place called House of Purpose.

Mr. Wallburg, despite his distaste for people snoopin’ around his practice, was kind enough to hand over security footage from Friday night so I could at least get a look at the bugger myself. I sat in the company maintenance room with my eyes fixed on a tiny black-and-white screen for almost an hour, watchin’ the individual particles dance around like monochromatic grains of sand. What I saw almost bored me to tears.

As expected, Rodney milled around the office like it was business as usual and took off in his dingy pickup truck at 5:13. He parked slightly too far away for me to make out his license plate number, but far as I was concerned, catchin’ a glimpse at the beast he drove was just as helpful. I couldn’t recall a single pickup in town that was the same obnoxious lime-green color as Mr. O’Meara’s. A man had to have serious balls to drive a truck like that.

With only one lead and enough caffeine to launch me to the moon, I finally scurried out of Mr. Wallberg’s hair before he kicked me out himself. He looked like the type of guy to glue his toupee to the top of his head cause he’d rather get a skin infection than be caught goin’ bald. And those types of people were scary.

Knowin’ I probably wasn’t welcome back, I piled into my rusted Wrangler and careened onto the freeway.

***

Second stop of the day was Rodney’s new church. The rickety white steeple looked horrifically out of place next to the lofty Norfolk apartments, its shingled roof crooked like a row of oblong teeth. This place may have been called House of Purpose, but to me the only purpose it seemed to be servin’ was as an eyesore.

My tires screeched against the asphalt and I buried my boots into the unkempt grass of the walkway. Would it really kill ’em to mow the lawn every now and then? Havin’ such an overgrown mess out front made the whole place look like a zombie apocalypse refuge. I avoided the weeds that threatened to tickle my shins and yanked on the weathered front doors.

The door was sealed tight like a virgin. I waited as a series of clicks and locks erupted from inside before revealin’ the gnarled face of a lady too young to be sportin’ so many wrinkles. She placed a spindly hand on one of the deadbolts.

Aren’t churches supposed to be open establishments? I thought to myself. Why the hell does this place have the Da Vinci Code cryptex on its front doors?

“Can I help you, sir?” The woman spoke with a churlish tongue and wrapped her fingers around her pendulum hips. “We’re about to start a mass.”

“Name’s Duke Baxter, Norfolk sheriff.” I tipped my hat courteously. “Real nice place ya got here. Love the gargoyles up at the front. Anyways, I was just wonderin’ if you happened to see this man come by anytime after Friday night. Maybe he stopped by for a Sunday service?” I produced Rodney’s fuzzy mug from my pocket and shoved the flyer in the woman’s face. “His momma said he’s a regular churchgoer here.”

The woman leaned in close to the paper, almost close enough to give Rodney a peck on the lips. I could practically see the smoke billowin’ out of her curlicue head.

“Yeah, that’s Rod O’Meara. Real nice kid. Now that you mention it, I reckon the last time I saw him was on Sunday. Came by for mass, then left straight after. Seemed kinda jumpy, if you ask me.”

A small crowd began to gather behind Little Miss Muffet. There were fifteen of ’em at least, hoverin’ in the background like paper lanterns, wrappin’ their formless bodies in the dark of the church. Ghoulish—only their eyes visible.

“Any other questions or will that be all? Like I said, I have a mass to start.”

I shifted my weight from side to side, suddenly put off by so many peepers lookin’ straight at me. What kinda mass was held in the dark? Everythin’ about this was raisin’ red flags.

“Can you recall if Rodney mentioned leavin’ town?” I asked. “Or did he say anything out of the ordinary? Anything that might strike you as odd?”

“Nope,” the woman snapped back. “Not to my knowledge. He was acting fairly normal.”

“But you just said he seemed jumpy.”

“Well . . . I don’t know!” She was startin’ to stammer. “You can’t just ask me about some random kid I saw two days ago and expect me to recall specific details. I have a whole church to run. I see lots of faces every day.”

I wagged a wary finger with disdain. “Hold on there, ma’am. You just called him a random kid. I thought Rodney was a member here. Shouldn’t you be able to distinguish the members from drifters?”

“Yes, but like I said, there’s a lot of people who come for service. Rodney’s new and I didn’t really know him that well.” There was a long pause while she exhaled, probably tryin’ to pacify her rattled nerves. Eventually, she piped up one more time and said, “The boy came for mass and left right after. That’s all I know. Hand to God.”

I let the words settle in the cracks of my brain. “If you say so,” I replied.

Miss Muffet suddenly reached for the door handles to lock her posse back into the dungeon, but I wasn’t done with my interrogation just yet. I leaned against the wooden entryway to prevent her from slammin’ the door in my face. I knew if it were up to that woman, I’d be kissin’ a set of wizened oak planks and bein’ formally ushered back to my car.

A bulbous vein began to sprout above Miss Muffet’s eyebrow the longer I stood there in the entryway, stiff and still as a dead fish. The splinters of the aged wood jabbed my forearm like porcupine needles but I grinned the pain away.

“I sincerely apologize for keepin’ you from your mass, but I just have one final question to ask.” I felt a wooden thorn draw blood. “From my understandin,’ aren’t churches supposed to be a welcomin’ sort of thing? Jesus walkin’ up to ya with open arms and all that jazz. You know, love thy neighbor and whatnot. If that’s the case, why are you so eager to shut me out? I ain’t posin’ any harm. Just askin’ some simple questions is all.”

The woman glanced back at her entourage, almost like she was lookin’ for guidance. Someone to feed her a script. “It’s nothing personal, sir,” she finally said. “Like I said, we have a private mass starting right about now. You just happened to come at a bad time. Sorry about the lack of hospitality. It’s nothing personal, really.”

The crowd shuffled uneasily. I counted ’em all up as fast as my eyes could manage, scrutinizin’ each one like little amoebas under a microscope. Twenty people in total to occupy fifty empty pews? Things were gettin’ more bizarre by the minute, but I clearly wasn’t gonna get anywhere with this woman’s defensive disposition. This investigation was best left up to another day. Hopefully one with a warrant.

Before I said farewell, my eyes lingered on a strange scar branded into the chest of a man with a beard like powdered steel wool. The open collar of his shirt teased a mess of rouge lines in his otherwise porcelain skin. As much as I wanted to stare, he flashed me a disapprovin’ scowl almost immediately and forced my gaze elsewhere. I could have sworn the man’s frown lines were deep enough to hide quarters.

“All right, then. I guess that’ll be all for now.” I offered the group a candy-apple smile and winked at Miss Muffet through my sunglasses. “Thank you for your time, ma’am. Have a blessed day.”

***

“I just don’t know,” I told my wife later that night. “The whole vibe of that church didn’t sit right with me. I think they know more about Rodney then they were lettin’ on. All of ’em were congregatin’ at the doors like a high school clique, not even sayin’ a word. Real secretive. Real quiet. One of ’em even had a creepy-lookin’ scar.”

“A scar?” Darlene’s brows raised with curiosity. “What’d it look like?”

I slipped the strap of her nightgown off her shoulder and used my finger to trace along the milky canvas beneath, surfacin’ goosebumps with each tender stroke. I outlined the strange markings of the bearded man’s scar on her chest to the best of my ability.

“Somethin’ like that,” I concluded. Darlene stared at me point-blank. “What is it?” I asked.

“Do that again, Duke. Draw it again.” I did what I was told and repeated the motion. “That looks like the number four to me. In Roman numerals.”

I pondered this for a moment. “Could be. Gettin’ a number tatted in Roman numerals is pretty common these days. Maybe this guy was too poor to afford the ink so he scratched it in himself. You know how broke some Norfolk people are.”

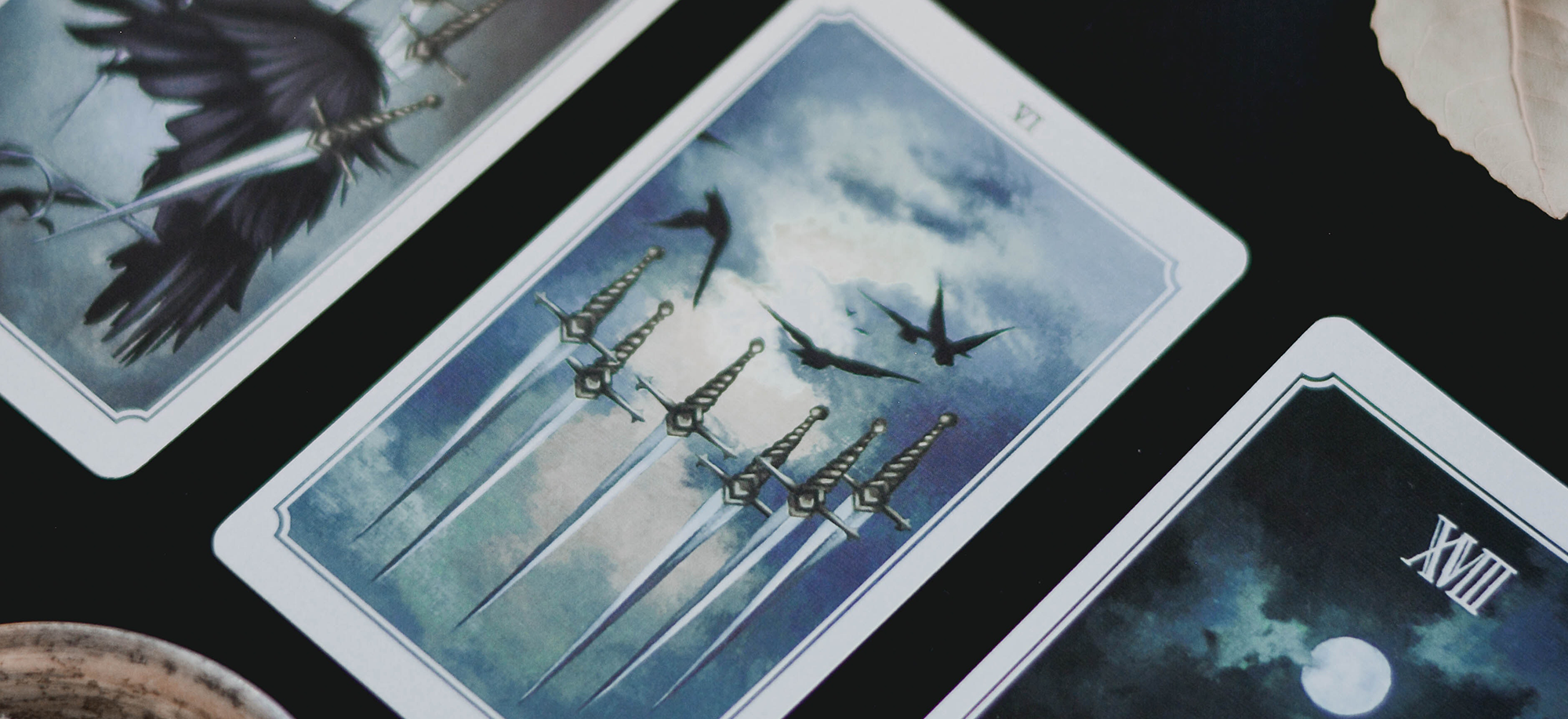

“It makes me think of tarot cards.” Darlene added thoughtfully. “Number four is the Emperor in the Major Arcana.”

“Come on, now.” I laughed to myself. “Don’t you think that’s a bit of a stretch? You’re the only person I know who’d see Roman numbers and automatically jump to something like that.”

Darlene shrugged. “I don’t know, Duke! I’m just spit balling.”

The mention of tarot cards took me back to ’98, back when Darlene was a professional fortune-teller. She gave me what looked like a hexed-up load of crock when I came to her carnival booth askin’ for my future one night. Two of swords this, six of suns that. As much as I thought her way with the cards was nothin’ but highway robbery, I found myself comin’ back the next night to talk to her. And the night after that. God only knows how much cash I threw away at her booth.

Despite connin’ me out of my savings, she drew me in with her warm doe-eyes, rich like cake batter and beggin’ me to go beyond a hello. We flirted all summer that way: me tryin’ to find another vague question to ask about my future and her leanin’ intentionally close to tell me about her findings. I suppose it only made sense for her to place some sorta spiritual meaning to an inscrutable scar on an old man’s body. As much as I loved my wife, sometimes she’d do anything to make connections to her past, no matter how disjointed the clues were.

“What are you going to do next?” Darlene’s mellifluous voice suddenly tore me away from my daydream.

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “The whole thing gave me the heebie-jeebies, but without any clues Mrs. O’Meara is gonna start naggin’ me for updates. I think I oughta go back to the church tomorrow. Undercover.”

“Undercover?”

“Yeah. And it best be me ’cause I don’t trust Trey or Al to do the job right. They haven’t seen what I’ve seen.”

“How would you manage that?” Darlene asked.

“Well, the church didn’t see much of me since I had my hat and sunglasses on. I figure I could shave off the ’stache, wear different clothes, and style my hair real proper. I’ll be a whole new man. I can even drop my voice a few octaves for good measure.”

“Oh, honey.” Darlene reached across the bed and kissed my face gingerly. I felt the ghost of her affection quickly grow cold, the June breeze fixin’ the remnants of her wet smooch as it drifted through the open window. She nestled her face in the crook of my neck and said: “You sure that’ll work?”

“Positive. Those people are dimwits, and like I said, most of ’em didn’t even get a good look at me. It’s only the leader I got to worry about.”

Darlene simply clucked her tongue with discontent. “Just be careful, okay?”

***

It was reachin’ that point in the year where all the summer days begin to slip into one another seamlessly. The afternoons melt into nebulous nights like a sweaty ice-cream cone cryin’ into your hands and before you know it, the week is over. Friday escaped me quietly and Saturday was just a fleeting blink of the eye. Before I knew it, it was time for Sunday mass at the House of Purpose.

I checked all the mental boxes for my undercover getup. Fresh haircut and dye job? Check. Shaved-off ’stache? Check. My trusty Colt hidden in the back of my belt? Also check. Drivin’ Darlene’s car instead of my own was the finishin’ touch to make myself look as foreign as possible.

Beads of perspiration crowned the nape of my neck as I trudged through the familiar verdant pathway, noddin’ my head to the twin gargoyles guardin’ the front door that was now wide open.

The expired air entered my lungs like poison, layers of dust kicked up from the shuffle of feet amongst the pews. Not knowin’ the proper church protocol, I sheepishly dunked my fingers in the birdbath upfront and signed a waterlogged cross onto my forehead.

The turnout was quaint, maybe forty people at best. There was a sea of unadulterated conversation and benevolent faces that made the cruel steeple from last week feel almost normal. “Jodie, did you hear? Kaden proposed to his girl last night!” a woman in the back exclaimed. “A real nice ring he got, too. You shoulda seen Sierra’s face. Them two are gonna make adorable babies!”

I sidled myself in the back and stayed zip-lipped ’til the priest took the podium.

To my surprise, the mass itself was also suspiciously average. Generic Jesus mumbo-jumbo, butchered Bible quotes, and at the end of the service, a generous distribution of the blandest wafers I’ve ever tasted. I was about ready to spit out the communion when Little Miss Muffet appeared behind me like the Holy Ghost itself.

“Why, hello there!” She greeted me with an artificial candor, blithely unaware of my true identity. “Thank you for showing up to our mass today. I noticed you’re new so I wanted to introduce myself. My name is Mitzy. I’m the orchestrator here.”

I cleared the spit in my throat and channeled a guttural tenor. “Nice to meet you, Mitzy. I just moved into the neighborhood and I was looking to get acquainted with a parish as soon as possible. I tried the other church on South Street but it wasn’t really what I was looking for. This place seems really nice, though. Love the atmosphere.”

“That’s great to hear!” Mitzy exclaimed. It was astoundin’ how starkly different her attitude was compared to my first visit. Either she truly did have somethin’ to hide or she just had a deep-seated hatred for cops.

“Are there any extracurriculars around here?” I probed. “Choir, Bible studies, maybe? I was really involved in my church back home and I’d like to keep that up if you don’t mind. My faith is really important to me.”

Mitzy smiled wide. “Well, I appreciate your interest. Where was your last parish located?”

“Chicago,” I lied. “Wife and I moved down south for a fresh start.”

“Amazing! Would you give me a moment to discuss things with my colleagues?”

“Of course. Take all the time you need.”

Mitzy promptly scuttled away and melded with a cluster of about twenty people hangin’ out by the altar. Her muffled whispers were too far away to discern, but even from a distance I was able to spot that disgruntled old man from last week. His face was concealed by the same raincloud beard and his hollow sockets held the beadiest set of eyes I ever did see. And then there was that scar, those jagged lines embedded in his chest . . .

IV. Number four.

“Well!” All of a sudden Mitzy was trottin’ back over to me with the power of Christ in her step. “You’re in luck because we just so happen to be looking for the twelfth member of our church group! Been looking for a while actually. Any interest, uh . . . ?”

“Max,” I said brusquely. “Name’s Max Smith.”

“Any interest, Max?”

“Oh, absolutely. It sounds fantastic, but . . . there’s already twenty of you here. How could you possibly be looking for member number twelve?”

“Well, we wanted an intimate group of twenty one. Each one of us is designed to have a special role in the church, and we just can’t quite find someone fit for position number twelve.” The damn woman unsheathed her serpentine smile, not even missin’ a beat. “But we all agreed that you have potential to be the perfect fit for our missing slot. I saw you reading from the hymn book during mass. You look like a real go-getter. If you’re not busy, you can come back tomorrow at noon for an interview of sorts. Whaddya say?”

I stuck my hand out for a hefty shake, strugglin’ to maintain my jaunty facade for even a second longer. “I say count me in.”

And then it happened. The split-second still of what I saw next would haunt me for the rest of the day and into the night.

Mitzy, her figure handsomely veiled in a white ruffled blouse made of fabric stiffer than rigor mortis, stepped forward in response to my handshake. As her arm began to creep further away from her shirt sleeve, I spotted an uncanny mark hidden close to her shoulder. There, cradled by the folds of starched polyester was a set of twin Xs carved into her forearm. Faded lines like two treasure markers on the map of her body, not much bigger than the size of a coin. I gulped like a parched man.

XX. Number twenty.

***

“You were right,” I told to Darlene over dinner. “About that weird scar on the old man. The leader of the church got the same shit on her skin but with a different number. A double X branded right into her arm, plain as day. Twenty.” I paused to stuff my face with mashed potatoes. “You know, they asked me to be a member of their church today. I have to come back tomorrow for some sort of interview.”

“Oh, Duke. The longer you talk, the more I’m starting to think you’re joining a cult instead of a church. What kind of people just invite a random guy to join without getting to know him a little?”

“I don’t know, but I can tell you one thing. I ain’t scarrin’ myself like that. No, sir. I am not an animal. I’d do anything for this job but that’s pushin’ it.”

“This sounds really dangerous, sweetie.” Darlene grabbed for my hand across the dinner table and squeezed tight, her dainty fingers interlockin’ with mine, her perfect knuckles round and smooth as marble. I squeezed back reassuringly and rubbed my thumb in the crook of her wrist in slow, rhythmic motions.

“I’ll be okay.”

“I just don’t like the sound of this woman,” she continued. “And the fact that Rodney went missing after going to mass at that same church last week? I don’t like it one bit. Why don’t you ask for help on the investigation? Having backup could be useful if things go awry.”

“No way. I’m lucky I slipped under that woman’s radar to begin with. There were a few times I thought she mighta seen through my disguise. Bringin’ in other people would just raise more suspicion. I gotta do this alone.”

“Fine. But whatever happens tomorrow, just promise me you’ll be safe.”

“I promise, baby. I promise.”

I caught my wife’s eyes to let her know I really meant it—those sober, snow-globe eyes, so pretty and wide with admiration. I kept this image fresh in the back of my mind the next mornin’ as I trudged through the thick brush of the steeple courtyard again, Colt tucked away quietly inside the back of my pants.

***

I rapped on the warped doors with apprehension. Mitzy emerged moments later with her horrid smile, all neat and plastered like it was some sort of sticker she kept over a petulant frown. The harsh rays of the mornin’ light turned her aquiline nose into a sundial, castin’ an awfully brutal shadow on the left side of her face. She glared with one eye plunged into darkness and beckoned me inside.

“How are you doing today, Max? You ready?”

I laughed briskly. “Ready as I’ll ever be.”

“Everyone here is really excited for this, you know. For our number twelve. We had someone try out the role on Friday, but unfortunately it didn’t work out.”

“And why’s that?” I dared to ask.

“He just wasn’t the right fit. Kid wasn’t cut out for the job.”

“Kid?” I questioned. “He was a kid?”

“Well, I use that word liberally. Not a real kid. Maybe twenty-two years old, twenty-four, if I’m being generous. Here, take a seat on this pew.”

The rest of the clan circled around me almost immediately. Their eyes were like laser beams—X-rays, even—each one burnin’ through my skin and into my bones with their red-hot stares. I felt the urge to cover up and groped at my flannel to hide my nipples, which weren’t even exposed to begin with.

“Here you go, dear.” Mitzy handed me a plastic cup. “Thought you might want some water before we start. Some people get nervous before initiation.”

“Thank you. Wait a minute, did you say initiation? I thought this was going to be an interview.”

“Truth be told, we did a little digging on you after mass yesterday.” She threw me an impish wink. “Didn’t wanna admit it, but I might as well be frank. I figured it’d be easier to skip the interview process and just look up your records online.”

I chuckled nervously. “And what’d you find?”

“A clean past. Squeaky clean, actually. No criminal record, good credit score. You really are a standout citizen, Mister Max Smith.”

I suddenly felt the walls close in on me and I couldn’t tell if my body was gettin’ bigger or the church was gettin’ smaller. I felt like Alice in the White Rabbit’s house. I hardly knew my left from my right and my feet were smashin’ through the windows and my head was poppin’ through the roof like a jack-in-the-box and I was spinnin’ round and round. Was it Alice in the Rabbit’s house or Alice in the glass bottle? Or was it when she was fallin’ through the tunnel at the start of the movie? I was spinnin’ so fast, I could’ve sworn Mitzy had laced my water but I hadn’t even taken a sip.

How could she possibly research my name if Max Smith wasn’t a real person? Either she had been playin’ along with my ruse this whole time or there was miraculously someone in town who perfectly fit the description of my pseudonym. Guessing by that grin on her face, I figured she had to have known from the very beginning. She had to. The bitch was makin’ a fool out of me and callin’ my bluff to prove she wasn’t as stupid as I thought she was.

“Mind if I hit the poop deck real fast?” I knew I needed to stand up and run but I was afraid I’d be too woozy to take a step.

“Sure thing. Mark will show you where the restrooms are.” A squat man with a rectangular face stepped forward. He awkwardly bumped into my backside and pressed his hand to my shoulder to regain his balance.

“Sorry, I’m a bit clumsy,” he said.

“Quite all right,” I choked out.

Mark waddled off toward the back of the church with my sloppy self in tow. I brushed past the altar, past the pews, and followed him into a comically large door under Jesus’s feet. Peekin’ out from his shirt collar was the engraving of yet another set of Roman numerals.

XXI. Number twenty one.

“Here you go,” he muttered.

“Thank you, sir.”

“We’ll be waiting at the front. Come out when you’re ready.”

As soon as his quadrate head disappeared into the prayer room, I reached for the Colt in my pants but was met with the terrifying squish of my ass. Somehow, some way, that little devil had managed to pluck the gun from my belt when he stumbled into my back.

That was no accident. They’re all in on it, each and every one of ’em…

I was now on a mission to find a makeshift weapon no matter how small, all the while reelin’ at the thought of the church’s dirty secrets. I knew somethin’ was wrong the moment I stepped foot on the property, the moment I was judged by those silent gargoyles. I felt it in my gut, with every cell in my body. I felt it eat away at my insides like a black disease. Malignant like acid, I felt it inside me.

I rummaged through the bathroom cabinets with tremblin’ fingers, shovin’ everythin’ aside in a panicked frenzy. Toilet paper flew to the floor like party streamers, soap pumps crashed below like fireworks.

“Come on, come on, you motherfucker,” I cursed under my breath. I didn’t even know what I was searchin’ for but I knew I was runnin’ out of time. I flew to the storage room with cheeks flushed like a smacked bottom, my whole face searin’ hot with a fever of fright. My body slunk through the city of cardboard boxes piled up to the sky, hopin’ to find a boxcutter or even a pair of scissors. All the while, I felt the fear grab hold of my stomach, twistin’ me up like taffy in a candy factory.

And then I saw his feet. A pair of dingy loafers stickin’ up straight, the body attached to them stashed away under a mountain of cardboard.

Trepidation was a demon in my blood as I tore away the boxes, revealin’ the grim face of a dead man. Inch-thick brows, button nose, matted brown hair curled up on the floor. I gasped. This was Rodney O’Meara, supine and lifeless before my very eyes.

“Shit!”

The longer I stared, the more ravenous the thing inside me became. It was a monster, grabbin’ hold of my lungs, pumpin’ em full of molasses fear—thick, dense, and unescapable. I gasped for oxygen all alone in that back room, inhalin’ rancid dust in the dim light. It took all my willpower to get a closer look at Rodney’s pallid body.

Purple blotches painted his fragile neck in what appeared to be a hangin’, the spots of indigo dye seepin’ through the layers of his skin like busted grapes. I just stood there paralyzed, thinkin’ of Darlene and her chocolate-brown eyes. I promised her I’d be safe, I promised her…

“Everything all right?” Mitzy’s voice sent me flyin’ through the roof.

“Fine and dandy, ma’am!” I cried.

“Whatcha doing back here? Got lost on your way to the restroom?”

I nodded, still stupefied. “Yep. You got me.”

“Happens all the time, I’m afraid. Come on, the folks are waiting for you up front.” She led me back to the prayer room and handed me that damned glass of water again. “All right. Here’s your card, Max. Whenever you’re ready, we’ll step into the confession room and get started.”

Mitzy placed a small plastic card in my palms like a priest dishin’ out bread. I twirled it around with my forefinger and thumb, fingers twitchin’ like a kid high on candy. As the card turned over in my hands, I spotted the face of an upside-down man crucified on a tree branch with his hands hangin’ at his sides. I gulped hard. Finally it all made sense.

Tarot card number twelve. The Hanged Man.

Nicki Cavender lives in Austin, TX, where most of her time is spent managing the operation of her household. But in the small and quiet hours of the night, she writes.

I often take Simon to the ocean. It calms him when all else fails. It’s odd because he usually hates loud noises, hates being wet, even hates sand, but he’s always loved the ocean. I’m used to Simon’s sensory oxymorons, but navigating them is still exhausting. Perhaps it’s the predictable push and pull of the waves as they play along the desolate beaches, or maybe it’s the whispered secrets of the wind carried by grumbling storms that always seem to loiter just offshore. Or perhaps those are the things that I love about the ocean, and maybe I’m the one in need of calming.

Preoccupied with this thought, my slow driving grows slower as I meander through the fog escorting me along the oceanside highway. The winding descent from our house toward the coast has always seemed more treacherous than it is, and I am relieved to finally emerge from the clouds and see the first glimpse of town. Of course, like always, I want to immediately turn around and go back home, but I don’t.

Instead, I bring the Jeep to a slow stop at the newly installed traffic light on the corner of Pacific and First Avenue, next to McMahen’s Lumber and the old Episcopal Church. My hands ache, and when I glance down, I realize I’m strangling the steering wheel. My clenched hands look much older than I expect, but I think they probably always have. Slowly releasing the wheel from my tight grasp, I take a deep breath and raise my eyes a few inches to look outside. The heat from the hood is rising in a transparent rainbow of dancing waves up into the fog, which has now coalesced into mist. Feeling the rumble of the aging Jeep beneath me, I look closer at the strange, floating motes of water. I’m transfixed by this mist, these suspended prisms that seem to magically hang in the air, defying gravity and distorting light. But then I realize that the windshield is wet, the mist isn’t floating, and my sense of wonder disappears.

“It’s never going to change,” he says.

“What?” I ask, startled. I glance up at the rearview mirror and into Simon’s dark eyes.

“The light,” he replies. “It’ll never be green. It’s blinking red.” I stare at him, my mind suspended. “Mom, nobody’s here,” he says,“ let’s go.”

“Oh, yeah, okay,” I say, released from my momentary freeze, but feeling a bit rattled. “Thanks, bud.” I smile at him for reassurance, but he has already looked away. I struggle to put the Jeep into gear and eventually persuade it to move. As I drive through town, I notice that the mist is gone.

Anxious, I glance up at the rearview again. Simon’s still there, in the same exact position.

“Hey, we’re almost there,” I tell him, not knowing if he’s listening, or if he is even aware. But I’ve grown accustomed to this uncertainty; I am almost comfortable in this limbo. Before I had Simon, I didn’t know that I could love somebody so fiercely and resent them so completely.

As we reach the ocean, I pull into the parking lot of the Sand Dune Pub, a block away from the nearest beach trail. Simon jumps out of the car, and I quickly grasp his small hand to cross the deserted street. The warmth of his touch is precious, but fleeting. I look down at our intertwined fingers, and I realize I don’t know where Simon begins and I end. I stumble, then stop, I feel the street beneath me swell up and lurch down like the motion of the waves.

“Hey, Mom,” Simon’s voice reaches out to me. “Can you smell the salt in the air?”

I inhale, I am here, I am grounded. I turn to him and nod.

“I can, too,” he says as he gently tugs my hand.

“Do you want to leave?” I ask.

“No,” he replies, and we continue to the trailhead. Before we walk down to the top of the dune, I take out my phone and look at the time, because I am waiting. In twenty minutes, the psychiatrist will call. I am waiting to talk about things like diagnoses and options. I am waiting to talk about Simon.

Simon, whose imaginary Auntie is most likely a hallucination. Simon, who often whispers that reality is a dream, and dreams are reality, and that he is most likely invincible but everybody else is not. Simon who screams. Simon who lies. Simon who apologizes. Simon who is so very hard to love.

At the dune we take off our shoes, leaving them in between patches of beach grass. Barefoot now, we walk through the stages of sand toward the water: hot and loose, warm and soft, cool and hard, cold and wet. When the surf skirts our feet, I turn to him, smile, and say, “You may go now.” Simon throws his head back and howls, and I know that he’ll probably be a wolf for the rest of the day. He runs away from me, his small body getting smaller, jumping and twirling and shouting nonsense at the air.

Left alone on the empty beach, I feel the cold, foamy surf teasing my toes. I watch a piece of slimy seaweed rush up and grab my ankle like a shackle. Panicking, I kick out and it releases, briefly caressing my foot as it slips away, plunging back into the darker water. I look up and see Simon dancing, kicking up sand. His blond curls bounce as he leaps and conducts some strange symphony. Simon doesn’t notice the dark clouds creeping closer, sneaking up, in concert with the rising tide. It is an insidious but inevitable storm.

Restless and weary, I walk back to the warm, soft sand and sit down. The sound of the waves is unrelenting. Farther down the beach, Simon has now dropped to all fours and is howling at something unseen. I push my hands into the sand. It’s still soft, but the impending storm clouds have stolen all the warmth.

The psychiatrist’s call is late. My phone rings and I’m irritated to see my sister Evie’s name on the screen. Anxious about the doctor’s call, I’m tempted to hit decline. But I eventually answer the phone.

“Hey.”

“Where are you?” Evie asks.

“Why?”

“I just wondered what you were up to, that’s all,” she says.

I hesitate briefly, then sigh. “I’m at the ocean, waiting for the psychiatrist to call.”

“Oh. Okay.” She pauses. “So, how do you feel?”

“Fine,” I reply. “Wait, what do you mean?”

“I mean, how do you feel about Simon? And the whole Auntie thing?”

“I don’t know. What do you think?” I ask her, the sandy wind starting to pull my hair around my face.

“Um . . . about Simon? Well, I think . . . I think you also had imaginary friends.”

I drag my fingers through the cooling sand and mumble, “Yeah, but I outgrew them.”

“Did you? And anyway, you also have depression,” Evie reminds me.

“Okay, but depression isn’t a real mental illness,” I tell her.

“It’s not?” Wind whips through the silence between us. The clouds are getting darker. The beach is getting colder. I pull my knees up to my chest. “Okay,” Evie says slowly. “You know what? I don’t even know what you’re trying to convince yourself of anymore. I mean, what do you really want?”

What do I want?

A wave crashes on the shore and races up the sand, stalking me, more aggressive than before. I watch it slip back down, shamelessly sucking energy, gaining strength for its next attempt. Maybe I should get up; maybe I should move.

“Hey, Nat,” I hear Evie’s voice say. “What if Simon’s just a weird kid? You could just leave it alone, just let it be.”

A wave races up. I’m suddenly drowning in decisions, overwhelmed with regret.

“Natalie?” Evie’s voice quietly asks. “Hey . . . can you smell the salt in the air?”

I take a deep breath. “Yes,” I reply.

I hear her sigh. “That’s good.”

“Yeah, okay, I get it. Listen, I have to go,” I mumble as I hang up.

I put my phone back in my pocket. The storm has taken advantage of my distraction and crept on shore. The ocean has rescinded its invitation and is howling a warning to me, ripping sand past my face. I search the beach for Simon and find him too far away. I squint into the burning edges of the rain. He is talking to a woman who seems familiar, but in a peculiar way. I yell his name as I run toward him, the unforgiving storm destroying my strength and drowning my voice. I watch Simon hug this strangely familiar stranger, this middle-aged woman who is jogging on a beach, in a storm. Oblivious to the winds raging around them, they both turn to me, smile, and wave. I am unmoored. Then Simon is running to me. The stranger is running away. My body is on fire. I cannot move; I begin to unravel. An eternity later, Simon reaches me. I collapse onto my knees and grab him, rocking and sobbing with the devastation of the waves.

Before Simon, I realize, I never knew true panic.

Eventually, I hear his pleading voice: “Mom, what’s wrong?”

I look at him. Cold rain begins to sting the heat coming off my face. “Wrong?” I whisper desperately. “Simon, who was that woman?”

Simon looks at me incredulously, “Mom, you know her. That was Auntie.”

I feel the sand beneath me swell up and lurch down with the motion of the violent waves. “Mom?” Simon gently cradles my face with his small hands. “Mom, can you smell the salt in the air?” I nod, tears running down my cheeks, settling in between his fingers. “I can, too,” he replies. He reaches down and gently tugs my hand.

“Do you want to leave?” I ask.

“Yes,” he says.

Hand in hand, we start the long walk up the beach in the rain, the ocean churning at our backs. I probably missed the psychiatrist’s call. I think about Evie’s advice, and then look down at my hand intertwined with Simon’s, and realize I am okay with that.

Simon looks at me, looking at our hands, and asks, “Hey, Mom, who were you talking to earlier?”

I glance down at him, smile, and say, “Your aunt Evie.”

He stops, stumbles, looks up at me, and asks, “Who?”

Angela has written fiction for entire life and also works a day job as an online marketing content director. She can be found on LinkedIn under her “real” name, Angela Chaney.

Aphrodite is hitting on the dealer again. You’d think the goddess of love would have a bit higher standards than a fifty-five-year-old nerdy poker dealer with some serious dandruff issues, but to each his own, I guess. Of course, the dealer is trying his best to ignore her because Aphrodite is not Aphrodite the gorgeous creature with flowing hair and rosy skin at the moment. For this tournament, she has chosen to inhabit the form of Chang, a retired Chinese businessman with a receding hairline and double chin. Chang is one of her favorite forms to take when we play poker, mostly because she can pretend to speak no English and ignore us all. Aphrodite can be a real snotty bitch. I can say that because I’m her brother. Kind of.

When it comes to us gods, you just never really know who’s related and how. There have been so many stories and legends and accounts of how we came into existence that even we’ve become a little confused. Pretty sure Aphrodite and I can both call Zeus our dad, which makes us siblings. But then there’s also that story that Aphrodite just rose from the sea on a giant scallop. Which is weird, but is it really any weirder than Athena bursting from Zeus’s forehead?

“Hermes,” Dionysus mutters out of the corner of his mouth. “It’s your turn.”

I shoot him a dirty look for using my real name. Knowing Dionysus, he’s already tanked and has completely forgotten that tonight I’m Garrett, a strapping young bodybuilder from Encino. Not too far from my normal self, but I always try to stay pretty true to form. Unlike good ol’ dad. You just never know how Zeus is going to show up to the games, and it’s often the source of some high-level wagering among the rest of us. I once won control of Australia for a decade just by successfully guessing he’d show up as Blanche, an elderly woman with blue hair and a dirty mouth. Blanche is one of my favorites of Zeus’s disguises. Not only does he look like a grandma when he’s Blanche, but he also seems to take on some grandmotherly characteristics. With Zeus, you take any warmth you can get.

I look at my pocket cards again. I don’t really need to look at them because I know damn well there’s a pair of queens under there. But I try to be consistent about looking at my pocket cards two or three times throughout a hand so as not to give away how strong they are. I look around the table and see that Poseidon, Hades, Ares, and I are the only ones still in before the flop. Ares’s raise of three hundred dollars successfully knocked out the rest of our family and Maurice, the poor bastard who somehow ended up at our table and has no idea he’s wandered into a hornet’s nest of ego, immortality, and straight-up sibling rivalry. Usually, when a mortal slips into the mix somehow, we’re able to intimidate him into leaving within a few hands, but Maurice is diligently hanging on. You’d almost respect him if he didn’t look like he was going to pee his pants at any given moment.

I call Ares’s raise instead of re-raising because you have to be careful when Hades and Ares are in a hand together. Those shitheads love to cheat. No matter which one wins, death and destruction are on the menu so they tend to “assist” each other whenever they get the chance.

The flop comes: king of diamonds, jack of spades, ten of hearts.

Artemis gasps dramatically. It’s anybody’s guess why, since the cards aren’t that startling and she isn’t even in the hand anymore, but that’s Artemis for you. Being the goddess of nothing too interesting (the moon, chastity, shit like that) and the twin sister of Apollo, the biggest do-gooder and perennial parental favorite, Artemis tries to get attention however she can. Which would also explain her disguise as a three-hundred-pound black woman with hot pink hair and a Chihuahua named Chimichanga on her lap.

It’s a decent flop for me as I’ve got an outside straight possibility, but not so good since one of the other dudes could have a king or ace and has flopped a stronger pair than I have. Not surprisingly, Hades bets and Ares raises again. The rest of the family is out, and for good reason. The last time Hades and Ares were in a betting war, the result was the Haiti earthquake of 2010. I’ve got a decent hand, though, and something about my attitude tonight makes me want to challenge them. It’s like that dorky kid who always gets taunted by the brutes in school—sometimes he just gets fed up and fights back, even though he knows it means he’s gonna get his ass handed to him.

I call, and the dealer flips up the turn: queen of spades. Now things are really getting interesting. I’ve got trip queens, but we’re one card shy of a straight on the board. If I was in the hand with any of my sisters or Dionysus, I’d know instantly if they had the straight. Even though we’ve been playing this game for thousands of years, they still haven’t figured out what a “poker face” is. But Hades and Ares are different. They’re so wild with their betting that you never know if they’re betting because they’re bluffing, they honestly have a monster hand, or if they’re just bored and want to spice things up. I remember a stretch of three hours where Ares never once looked at his pocket cards and still raised every blind. It made Apollo so angry that he had to go play the slots to calm down.

Hades bets. Ares raises. Artemis gasps. I can’t throw away trip queens, even with the possible straight on the table. Not with these two loose cannons. I call the bet, knowing damn well that an all-in bet will not deter either of my brothers, even if they don’t have squat.

“Whatcha got, my boy?” Zeus suddenly appears behind me and puts a hand on my shoulder. Tonight he’s decided to confuse the shit out of everyone by appearing as Ricardo Montalban, the actor from Fantasy Island who just happens to have been dead since 2009. He tried to get our mom to disguise herself as Tattoo, but Hera told him to shove it. When you’re out knocking up mortal chicks every chance you get, you usually don’t have much luck convincing your wife to do anything.

“I have a royal flush, Dad,” I say drily.